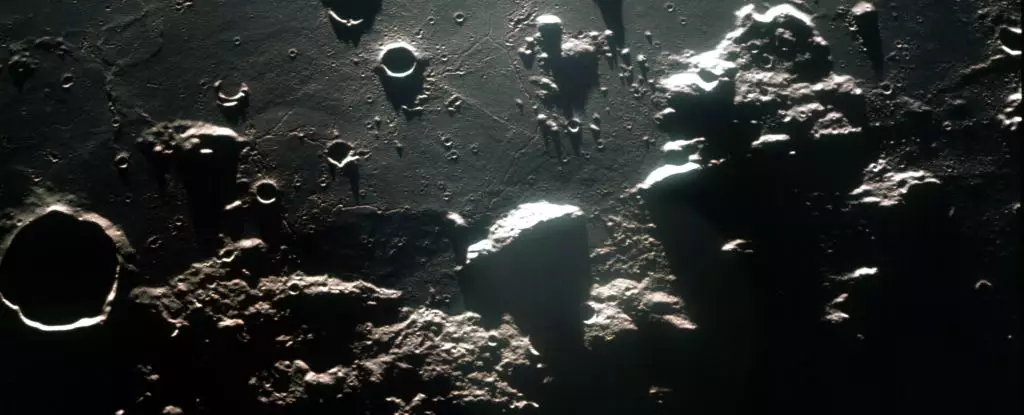

For centuries, mankind has gazed at the Moon, captivated by its ethereal glow and mysterious surface. Recent scientific advancements have revealed that this celestial body, often perceived as a barren and dry landscape, may in fact be hiding significant amounts of water. A comprehensive analysis of mineralogical maps has unveiled the presence of water and hydroxyl—two hydrogen and oxygen molecules—scattered across various lunar terrains and latitudes. This groundbreaking discovery poses essential implications for understanding the Moon’s geological narrative and its potential role in future human exploration.

Traditionally, scientists posited that substantial reservoirs of water existed primarily in the Moon’s polar regions, sheltered deep within shadowy craters. However, as planetary scientist Roger Clark from the Planetary Science Institute emphasizes, recent findings indicate that water can also be discovered nearer to the equator, heightening prospects for future lunar missions. This development could change the landscape of lunar exploration, as astronauts may not need to venture into the frigid, permanently shadowed areas of the poles in their quest for water.

Despite its reputation for aridity, the Moon possesses neither lakes nor rivers; instead, it presents a more complex narrative. Although the surface appears waterless, studies increasingly point to vast underground reserves, with prior inquiries revealing that much of this H2O might lurk in polar craters, shielded from direct sunlight. Clark’s recent investigations shift the focus towards a more comprehensive understanding of the Moon’s water distribution—an essential factor in both geological research and prospective lunar habitation.

At the heart of this discovery is the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) instrument onboard the Chandrayaan-1 mission, which orbited our satellite in 2008 and 2009. Utilizing advanced spectroscopic imaging technology, M3 analyzed the infrared light reflecting off the Moon’s surface to identify water and hydroxyl signatures across various lunar landscapes. This data illustrated that while water molecules are present, their concentration appears diminished in the darker, basaltic regions known as lunar mares.

Importantly, water on the Moon is not static. The ongoing interaction of solar radiation and cratering events plays a crucial role in water’s lifecycle on the lunar surface. When lunar rock experiences impacts, it exposes water-rich materials, but these materials degrade over time due to solar wind radiation, a process observed to occur over millions of years. While the H2O evaporates, hydroxyl remains, indicating the Moon’s continued interaction with sources of hydrogen and oxygen, suggesting a dynamic, albeit slow, geological activity that fosters these essential compounds.

Clark’s findings suggest that both volcanic activities and impactful events serve as mechanisms for redistributing water-rich materials on the Moon’s surface. This duality reflects a complex geology that offers valuable insights into the Moon’s physical development. Particularly compelling is the revelation that the characteristics of certain lunar rocks—specifically, pyroxene—fluctuate based on the sun’s angle, providing hints about the Moon’s geological intricacies. While earlier interpretations indicated potential mobility of water, new analyses imply that this motion may not be as extensive as previously believed.

Moreover, the discovery of water’s relationship with peculiar lunar swirls presents another layer of intrigue. These enigmatic patterns have puzzled scientists for years, and Clark’s team found that these swirls are significantly water-deficient, prompting questions about their formation and geological processes. The data suggests that some of these markings may represent ancient swirls that have eroded over time, presenting an opportunity to decipher their origins and the processes that shaped them.

Ultimately, this new understanding of water on the Moon opens groundbreaking prospects for future lunar explorers. With hydroxyl-rich minerals potentially providing a water source, astronauts have the exciting possibility of deriving water from the very rocks they explore. This reinforces the notion that the Moon can not only serve as a base for further space explorations but also as a sustainable environment for future human habitation.

As we continue to advance our understanding of lunar geology, we bring ourselves closer to unraveling the mysteries of our nearest celestial neighbor. The revelation of widespread water distribution could turn the Moon from a mere distant object of fascination into a stepping stone for humanity’s next great leap into the cosmos. With each scientific study, we bolster our quest for knowledge about this ancient, yet ever-evolving satellite.