The narrative of the plague is not merely a history of sickness and death but a compelling chronicle of microbial evolution and human resilience. Recent investigations reveal a startling revelation: the Yersinia pestis bacterium, responsible for the notorious pandemics throughout history, has undergone evolutionary changes that have made it less lethal over the centuries. Such adaptations have allowed it to persist, adapting to its human hosts and ensuring its survival through three significant outbreaks—The Plague of Justinian, the Black Death, and the third pandemic that emerged in the 1850s. This historical resilience not only contextualizes the past but poses relevant implications for understanding how pathogens may adapt in future outbreaks.

Mechanisms of Virulence Reduction

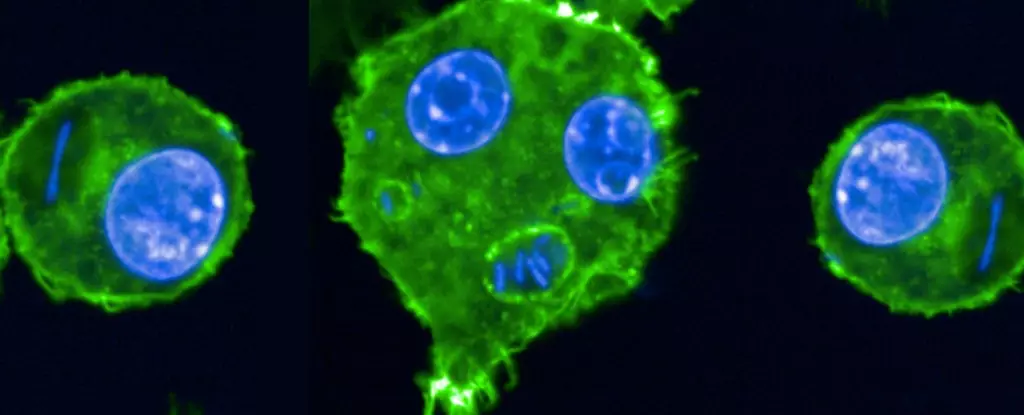

Researchers led by microbiologist Javier Pizarro-Cerda have ventured into the genetic underpinnings of these bacteria, uncovering a significant trend: the organisms have become less virulent as time progressed. The analysis of Yersinia pestis across various historical samples illustrates a biochemical shift wherein the severity of infections has diminished. By diminishing its virulence, the bacterium has strategically prolonged its ability to infect the human population. This adaptive evolution acts as a double-edged sword; while it lessens the immediate risk of mortality, it simultaneously enhances the bacterium’s potential for sustained transmission among individuals.

With implications echoing through centuries, this study accentuates a biological principle of adaptability that can be observed within various pathogens. The experiment that involved inoculating rats with historical strains of the plague showed that reduced virulence led to a prolonged infection lifecycle, further perpetuating the spread of disease. It raises a crucial consideration: Could this knowledge of historical adaptations inform current approaches to combat not only the plague but other emerging diseases?

Lessons for Modern Medicine

In an era dominated by advanced antibiotic therapies, with Yersinia pestis now manageable through modern medical intervention, the findings of this study invite attention to deeper preventive measures. While antibiotics remain vital in treating plague cases, understanding how pathogens evolve may redefine strategies for managing not only existing diseases but also emerging threats on the horizon. The adaptability of bacteria challenges health professionals and researchers to continuously evaluate their responses to infections, fostering innovative pathways in public health policies.

Pizarro-Cerda remarks that grasping the “how” of these adaptations provides a robust foundation for fortifying our defense mechanisms against infectious diseases. The lessons drawn from historical epidemics could reshape our understanding of pathogen behavior and demand that we remain vigilant and proactive about potential viral mutations in an interconnected world. The narrative of the plague, steeped in lessons of survival, adaptation, and the ongoing struggle between human health and bacterial threat, continues to echo in contemporary discourse.