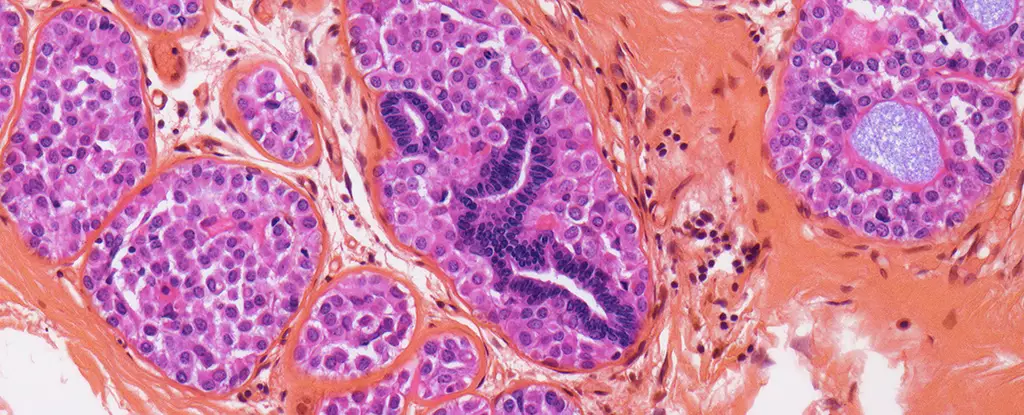

The common narrative surrounding cancer treatments, especially breast cancer, often gravitates toward the cognitive side effects, notably the phenomenon popularly dubbed “chemobrain,” which describes impairments in memory and concentration experienced during and after therapy. For decades, these concerns have dominated discussions about the neurological aftermath of cancer survival, painting a rather grim picture of long-term cognitive health. Yet, emerging research from South Korea introduces a fascinating and somewhat counterintuitive perspective: surviving breast cancer—and the treatments that accompany it—might actually correlate with a modestly reduced risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease later in life.

This revelation compels us to reconsider simplistic views on the long-term cognitive impacts of cancer therapies. Instead of focusing only on short-term cognitive impairments, it beckons scientists and clinicians alike to explore nuanced, sometimes paradoxical effects treatments could have on brain health over the years.

Analyzing the Link: Breast Cancer Survival and Alzheimer’s Incidence

The Korean study rigorously analyzed health data from over 70,000 breast cancer survivors alongside nearly 180,000 control participants without cancer, monitoring outcomes over an average of 7.3 years. The researchers observed an 8% lower incidence of Alzheimer’s disease among breast cancer survivors when compared to those without cancer histories. Although this difference may appear modest at first glance—translating to roughly 0.18 fewer cases of Alzheimer’s per 1,000 women annually—it becomes more compelling given the sheer scale of the populations involved and the demographic weight of Alzheimer’s on aging societies.

What’s especially thought-provoking is the apparent role of radiation therapy in this risk reduction. Contrary to worries that cancer treatments might accelerate cognitive decline, radiation exposure in this context seems linked with a diminished likelihood of Alzheimer’s diagnosis, at least in the initial years following therapy. The underlying mechanisms remain speculative, but previous studies hint that radiation’s anti-inflammatory effects in the brain might contribute, potentially mitigating neurodegenerative processes.

Challenging Preconceptions About Long-Term Cognitive Impact

The idea that cancer treatments could simultaneously induce short-term cognitive struggles and long-term neuroprotective effects challenges existing dogma. Common reports of cognitive fog in breast cancer survivors are undeniable and must be taken seriously by healthcare providers. However, conflating these transient symptoms with irreversible, progressive neurodegeneration such as Alzheimer’s may oversimplify a complex interplay of biology and treatment effects.

Importantly, the Korean researchers caution that their observational data cannot establish causality—survival bias and other confounders might influence the outcomes. Perhaps women rid of breast cancer, and engaged with healthcare systems closely, receive better monitoring or healthier lifestyle interventions post-treatment, factors that could themselves lower Alzheimer’s risk. Nonetheless, the findings underscore a critical research gap: an urgent need for long-term, mechanistic studies teasing apart how cancer therapies affect the aging brain.

Broader Implications and Future Directions

The research injects a glimmer of optimism into breast cancer survivorship discourse and Alzheimer’s prevention strategies alike. Breast cancer, despite being the most common cancer in women worldwide, boasts improving survival rates, largely thanks to early detection and advanced treatments. Thus, understanding the secondary health ramifications for survivors is vital to comprehensive patient care.

If certain treatments—like radiation—have unexpected benefits for neurodegenerative risk, this could pave the way for novel therapeutic approaches or adjunctive interventions targeting Alzheimer’s disease. It also invites a broader reconsideration of inflammation’s role in neurodegeneration; treatments reducing systemic or neuroinflammation could confer cognitive resilience, a hypothesis worth exploring.

While it’s too early to transform clinical guidelines based on these findings alone, the study encourages clinicians, researchers, and policymakers to adopt a more nuanced stance when addressing cognitive health post-cancer. Rather than viewing cancer therapies as exclusively harmful to brain function, we ought to recognize their complex, sometimes beneficial, influence on long-term neurological outcomes.

In the end, the intersection of oncology and neurodegeneration is a rich, underexplored field. This study from South Korea offers a valuable data point—one that, if confirmed and expanded upon, might inspire transformative shifts in how we conceptualize and manage post-cancer cognitive health, ultimately sparking hope for millions of survivors facing dual threats from cancer and dementia alike.