In emergency situations where a person’s heart stops beating, every second counts. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can be the difference between life and death, maintaining blood flow and oxygen supply to vital organs until professional medical help arrives. Despite the life-saving potential of CPR, there exists a troubling disparity in how bystanders respond to cardiac arrest based on the gender of the victim. A recent Australian study highlighted this issue, revealing that bystanders are more likely to perform CPR on men than on women. The question arises: what factors contribute to this alarming trend?

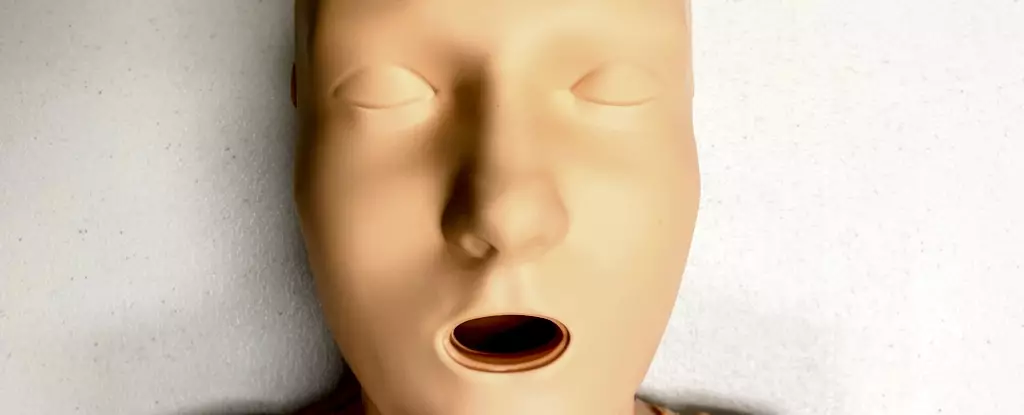

Statistics are telling. Research indicates that from 2017 to 2019, out of 4,491 cardiac arrest cases studied, 74% of men received CPR while only 65% of women did. This significant gap poses critical questions regarding societal behaviors and biases. One potential factor is the training methods used to teach CPR. Traditionally, CPR training mannequins — or manikins — are predominantly flat-chested, with a striking 95% of available models lacking any anatomical differences that represent female bodies. While the technique for performing CPR does not differ based on gender, the aesthetics of training tools can influence who is perceived as deserving of life-saving intervention.

The predominant use of male-dominated training materials sends a subtle but powerful message: male bodies are the norm, while female bodies are an afterthought. This bias is reflected in CPR scenarios where witnesses might hesitate to act because they may feel uncomfortable with the thought of physically intervening on a woman. Furthermore, factors such as fear of accusations related to sexual harassment and misconceptions about women being more fragile complicate the scene. The reality is that hesitation in these critical moments can exacerbate the already dire circumstances of a cardiac arrest.

Women and Cardiovascular Disease: An Alarming Reality

Women are disproportionately affected by heart disease, stroke, and other cardiovascular disorders, which are among the leading causes of death. Yet, women suffering cardiac arrests outside a hospital setting are statistically 10% less likely to receive CPR compared to their male counterparts. Alarmingly, even when women do receive CPR, their survival rates and outcomes — including potential brain damage — present a stark disparity. The need for equal recognition and treatment in medical emergencies cannot be overstated, especially considering the broader implications for transgender and non-binary individuals who also face inequities in healthcare.

A critical examination of CPR training methods reveals that the majority of available manikins are not representative of the diverse demographic they aim to teach. In 2023, an investigation identified only 20 CPR manikins on the global market, of which only five (25%) were marketed as “female” — with just one featuring breasts. This lack of diversity extends beyond gender, as most training manikins are also overwhelmingly of a singular skin tone and body type. Without representation, trainees may develop biases that affect their willingness to intervene in emergencies involving women or individuals who do not conform to traditional gender norms.

CPR can be performed effectively irrespective of one’s physical characteristics. To ensure that bystanders are prepared to act in emergencies involving any individual, training must evolve to encompass a variety of body types and features that reflect real-life scenarios. Educational programs focusing on recognizing cardiac arrest symptoms — such as unresponsiveness and absence of proper breathing — should be made more prevalent in community workshops.

Practical steps to perform CPR include placing the heel of one hand on the center of the chest, interlocking fingers, maintaining straight arms, and applying pressure at a depth of about 5cm, at a tempo of 100-120 compressions per minute. Furthermore, while a woman’s bra may pose a minor hurdle when using a defibrillator, the essential point remains that immediate action is always preferable to hesitance.

The research suggests an undeniable necessity for an overhaul of CPR training materials to include a diverse range of manikins that accurately represent all body types and genders. This is a vital step toward ensuring that everyone, regardless of gender, receives life-saving care in emergencies. Ultimately, enhancing education about cardiovascular risks specific to women and others will promote greater awareness and equality in emergency response practices. In doing so, we create a more inclusive environment, fostering confidence in bystander action that could save countless lives.